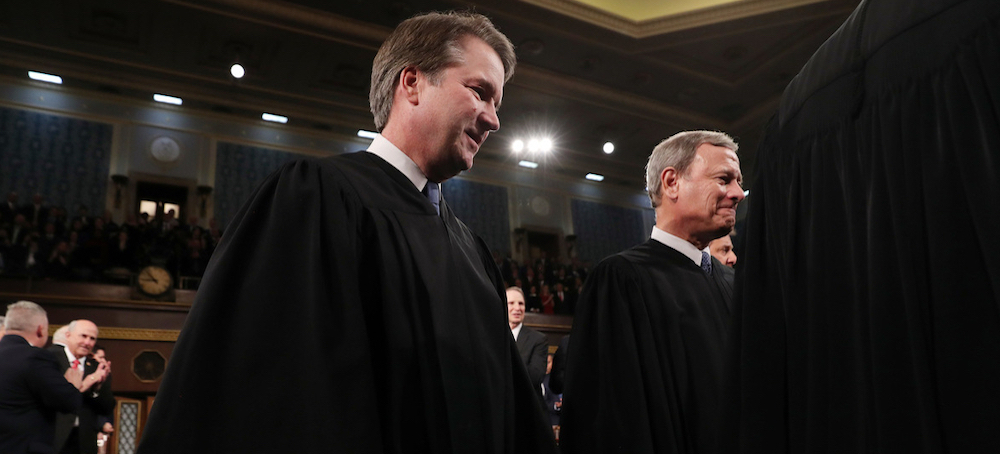

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

The Supreme Court is on a collision course with itself, and it’s not clear that the justices even know it. We are now witnessing a five-car pileup of Trump–slash–Jan. 6 cases that will either be heard by the Supreme Court or land on their white marble steps in the coming weeks. The court has already agreed to hear the case of Joseph Fischer, the former Pennsylvania cop accused of taking part in the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and assaulting police officers, to determine the scope of prosecutions for obstructing an official proceeding. The court’s already flirting with hearing a direct appeal by special counsel Jack Smith to speedily resolve Trump’s claims to absolute immunity for his actions in attempting to overturn the 2020 election. And a game-changer of a case came out of the Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday that would knock the former president off of the Republican primary ballot in that state as a consequence of his involvement in the insurrection attempt on Jan. 6, which would also critically apply to the general election ballot next November. That ruling has to be settled by the high court in order to forestall, or affirm, other states’ efforts to do the same thing. Potential appeals of gag orders in criminal suits and doofy immunity claims in the E. Jean Carroll suit are all also winging their way to Chief Justice John Roberts’ workstation, and it’s not even 2024 yet.

In the meantime, the justices cannot seem to catch a break when it comes to being caught behaving terribly. In addition to the bottomless evidence of judicial freebies and junkets that were not disclosed by justices bound by both disclosure and recusal rules, the past few weeks have brought bombshell reporting from ProPublica about the ways in which the body meant to police the court was mostly just laying around the henhouse hoping for a good scratch behind the ears.* Then this week, ProPublica produced another in-depth report of how a bunch of millionaires and conservative activists—afraid that Justice Clarence Thomas might leave the court if he didn’t get a pay raise and nice lifestyle perks—conspired to get him pay raises and lifestyle perks. This effort somehow was blessed by (surprise!) members of Congress; the judiciary’s top administrative official, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell; and others who understood perfectly that you needn’t hate the player, or the game, you really just need to take him on island cruises to Indonesia to keep him in the league.

Added to that, there’s the phenomenally reported New York Times story from last week about the ways in which the Supreme Court’s conservative members manipulated and distorted the outcome in the Dobbs case overturning Roe v. Wade in order to try to keep up appearances, even as they phoned in their work on the case to achieve the partisan outcomes for which they were seated. Even if you fully believed all the nonsense about nonbinding ethics codes that are enforced by mindpower, Cool Whip, and promises of good faith, it just isn’t possible to read the stories about 20 years of partisanship, pay-to-play, and the erosion of norms of judicial humility and restraint on the part of the MAGA wing of the court and still feel confident that this is the body to which one wants to entrust the major electoral outcomes of the coming year.

The two stories—political corruption and political cases—are so inextricably connected that one almost wants to weep at the rate at which they have been force-multiplied as disasters in the making in a matter of weeks, and not because the press is out to discredit the high court, but because the court has been so hellbent on discrediting itself and then refusing to cop to it. It’s the political and financial dirty work of two decades, coming to light in the span of one year, that the court has brought on itself at the moment in which it should have been beyond reproach.

In the coming months, Thomas will have to decide whether his wife’s text messages around and participation in the very same insurrection for which Trump is being removed from the Colorado primary ballot mean he should recuse himself from that case. He will allow himself to pass judgment on whether her subsequent insistence that the 2020 election was stolen might just make it improper for him to hear the Colorado case. The new code of conduct recently embraced (no, really) by the court requires that the justices disqualify themselves from an appeal if their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” Moreover, justices should be mindful as to whether their spouse has “an interest that could be substantially affected by the outcome of the proceeding” or is “likely to be a material witness in the proceeding.” We know Thomas is capable of applying this test to himself in theory because, for reasons unknown, he removed himself from a case last October involving John Eastman, principal architect of one of the key legal plots to keep Trump in power. But will he do the same when the stakes are much, much higher? And why on God’s Earth is he being permitted to decide these high-stakes questions at all?

Also in the coming months, with public mistrust for the integrity and character of some of the justices at record lows, the justices will have to help the public understand why they should be trusted to engage in sober, principled deliberations of thorny questions when reporting shows that at least some of them take 10 minutes to read 98 pages, that decisions in major cases are ends-driven and political, and that a couple of them are more than willing to distort the record to cover up for that fact. In the coming months, the public will have to sit with the fact that Justice Samuel Alito told Wall Street Journal opinion writers that the court is untouchable by Congress and with the fact that when the Senate sought testimony from the chief justice last year he just refused to show up. And the public will have to just get really comfortable with the fact that this imperial court thinks that kind of thing is fine.

One of the most striking aspects of the Colorado Supreme Court’s ruling is how much of the 213-page opinion is devoted to institutional humility: Are the issues justiciable? Is this a political question better resolved by the political branches? Is it even appropriate for a court to resolve issues of such enormous national import? While the 4–3 majority of the Colorado court came down with a “yes” on each of these issues, you can’t say they didn’t take them seriously:

We do not reach these conclusions lightly. We are mindful of the magnitude and weight of the questions now before us. We are likewise mindful of our solemn duty to apply the law, without fear or favor, and without being swayed by public reaction to the decisions that the law mandates we reach. We are also cognizant that we travel in uncharted territory, and that this case presents several issues of first impression.

Agree or disagree with the conclusions of that court, the deep seriousness of purpose and institutional humility pervading that opinion is palpable. Compare that tone to the self-certainty on display from some of the members of the highest court in the land, who, when caught out in self-dealing and dishonesty, reject any effort to rein them in and persist in declaiming their own infallibility.

For years, some of the most vocal critics of the court’s ethical lapses, its lack of transparency, and its refusals to take seriously its own brokenness and errors, have warned that the day would come when an election would be decided by a body that has refused to clean house and has blamed the press and the academy for the stench of its own illegitimacy. The worry wasn’t that the court would decide the election; that seems almost inevitable. The worry was that the public, grown weary of the stench, would not abide by their decision.

Lavish world cruises, secret deals with moneyed donors, threats to step down unless someone ponied up with a pay raise, fishing trips with parties who have business before the court, an amicus brief industrial complex wholly bought and paid for by billionaire donations, leaked drafts, and secret speeches are not the stuff of constitutional democracy, or infallibility, or finality. When the hyperpolitical supercharged Trump cases catch up with the court—and that is beginning to happen, right now, this week—all that stench will run headlong into the questions about why the husband of the woman who went to the pep rally for the insurrection and the folks who lied to us all about Dobbs are objective enough to decide the outcome of an election. The same people entrusted with the protecting the reputation of the court have blundered into being wholly responsible for protecting democracy. Not one thing suggests they will take the latter any more seriously than they took the former.

No comments:

Post a Comment